Cagliostros’ Apothecary – Cellar – Retrospection and Anatomy

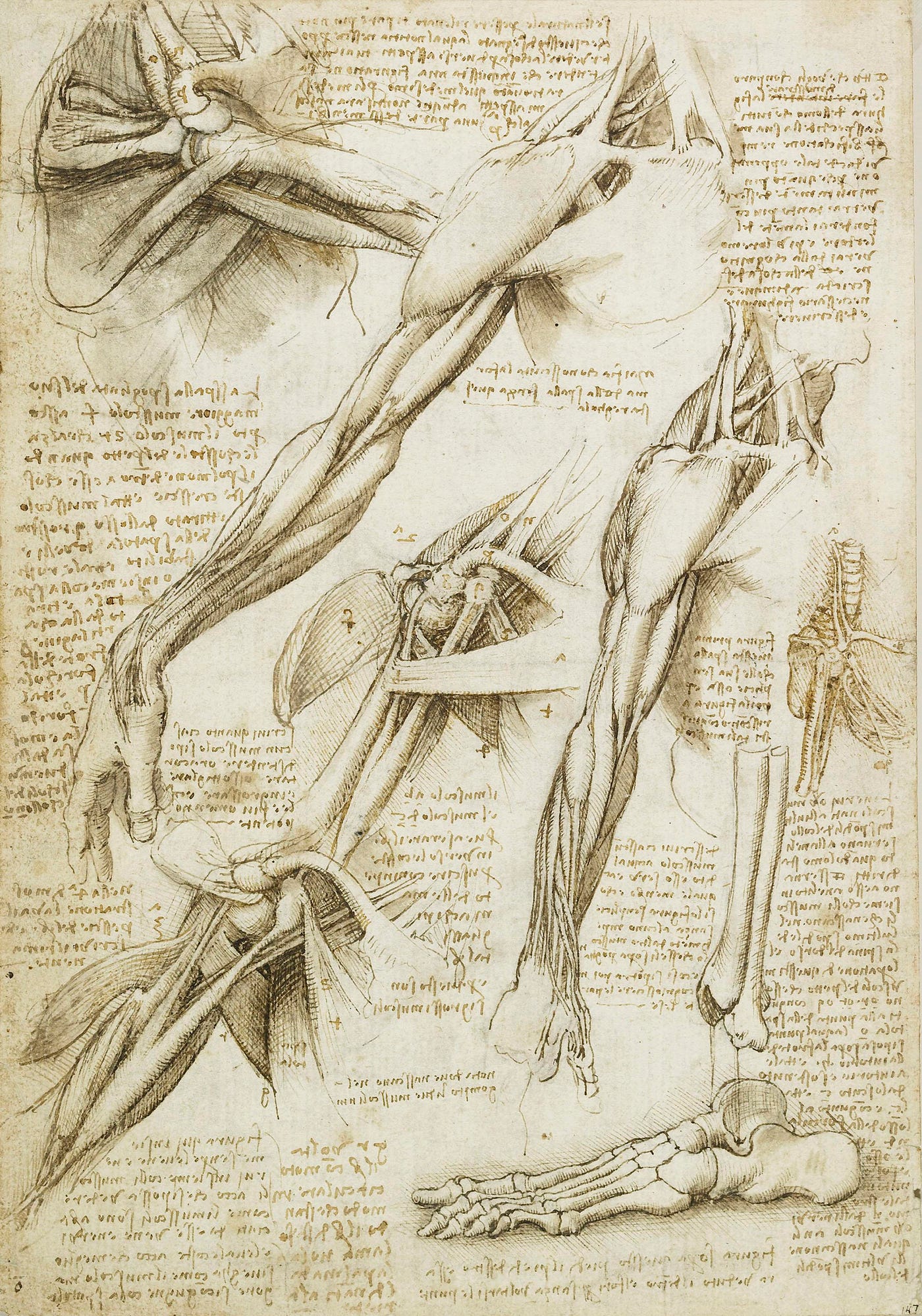

Nicolaus carefully exposed more of his subject and adjusted the placement of the lighting to eliminate shadows. He wiped his hands on a scrap of cloth and adjusted the lenses perched on his nose to define the details more clearly. He studied his current drawing, then began to add further details relating to the mechanical function of the skeleton and how the muscles connected to it. He noted no serious deformities, and the variations present were well within his experience.

As he drew his mind wandered to his time at the Great Library. He had arrived not realizing his views were so unorthodox.

His father, a good if distant man had sent him to his paternal grandfather to receive further education, possibly because even then he was seen to have certain gifts. Through family connections he was given an opportunity to learn in the workshop of Correv Aerdn, a learned man of the time. Working first as a shop’s boy and then as a true apprentice when his skills became apparent, he remained for eight years. He was exposed to much theoretical training and technical skills including drafting, chymistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leatherwork, mechanics and woodwork; as well as artistic skills such as drawing, painting, sculpting and modeling. By his twentieth year he was registered as a master in the guild of artists and of medicine. But it was his gifts in Alchemy that attracted the attention of the Library of Orb.

In fact, he mused, it had only been his contributions in Alchemy that had saved him from censure or even disgrace, as looked back now from a wiser perspective. The gifted were allowed eccentricity.

He had found it difficult to support the theories of bodily humours that held sway, he personally abandoned the ‘accepted’ physiological explanations of bodily functions. Simple observations proved that humours were not located in cerebral spaces or ventricles. He rigorously documented that the humours were not contained in the heart or the liver, and that it was in fact, the heart that defined the circulatory system. He created models of the cerebral ventricles with the use of melted wax and constructed a glass aorta to observe the circulation of blood through the heart by using water and seeds to watch flow patterns.

But much as there was religious dogma, the ‘men of science’ felt they had reached a pinnacle of understanding and the great discoveries were done. His focus on observation and experimentation to test the claims of the past and to find the new was considered arrogant. Breakthroughs in alchemy on the other hand were viewed as gifted synthesis of past works, easily done with the nature of chymistry.

Nicolaus continued to draw but his efforts became fierce and abrupt, compromised by memory. Until he stopped mid-stroke and calmed himself and began again.

He had left then, to see the world outside the cloistered Library. He had traveled extensively to see if the ‘facts’ so carefully entombed on the shelves of that great center of learning were in fact to be trusted. And he had found much embellishment, fakery and truth while broadening his own experience. He had had to work as he went, becoming an engineer and an architect and other things less savoury. In fact, his tunic had been tied over so many duties and services that it would shock his old teachers.

Nicolaus put the finishing touch on the drawing and placed it with a considerable stack of others before taking a clean sheet and beginning anew.

“Let us see if Felfar use leaves a trace, shall we?”